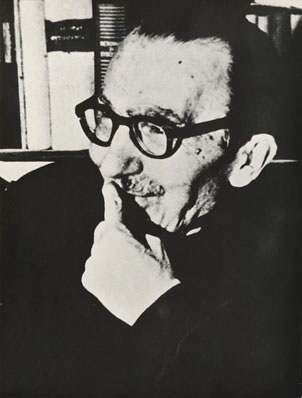

Emigration and Recognition (1946-1957)

In the summer of 1946, Kazantzakis set out on what later turned out to be his final journey to Europe. After staying in England for a while, as a guest of the British Council, he moved to Paris, where he was appointed as a literary advisor to UNESCO.

In March 1948 he resigned to settle permanently in Antibes on the French Côte d’Azur. The closing decade of his life was equally intense and creative; having gained international recognition, he wrote novels and plays, translated books and went on travels.

From 1951 onwards his health went into steady decline. He lost his right eye, and on several occasions was admitted to the University of Freiburg Clinic to undergo treatment for the benign lymphatic leukaemia that plagued him.

Nevertheless, he began working with Kimon Friar on the English translation of the Odyssey, a work which provoked intense reaction among clerical circles and led to demands that he be prosecuted.

In England

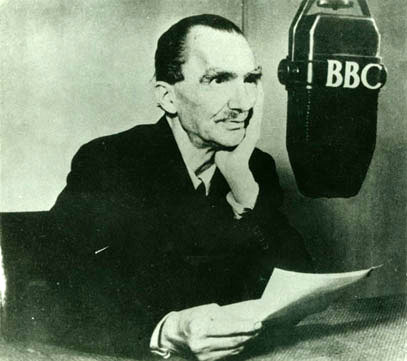

While in England, Kazantzakis planned to meet leading intellectuals and artists to discuss post-war problems relating to culture. In September 1946 these meetings gave rise to his appeal to intellectuals the world over to found an “Internationale of the Spirit”, reflecting international concern in the wake of the bombing of Hiroshima.

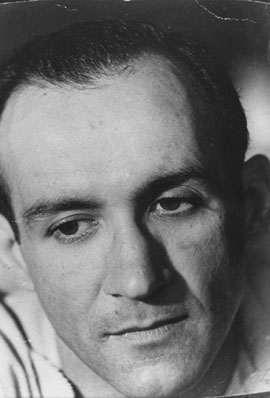

At the same time he was invited interviewed on BBC radio, following an invitation from Michalis Cacoyiannis. He spoke on George Bernard Shaw (then celebrating his ninetieth birthday), also referring to Angelos Sikelianos and his nomination for the Nobel Prize for Literature, and calling on intellectuals worldwide to work together in the service of peace and the restoration of humanitarian values in the wake of the horrors of war.

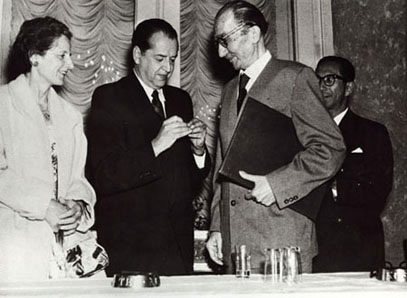

Recognition of his peace work came in the form of the Peace Prize awarded to him in Vienna in 1956.

Antibes

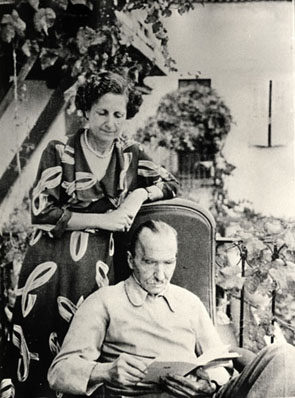

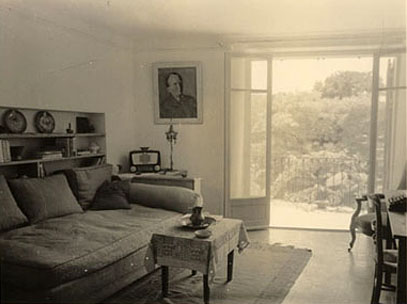

In June 1948 the Kazantzakis couple settled in Antibes on the Côte d’Azur, where they bought their own house in 1954.

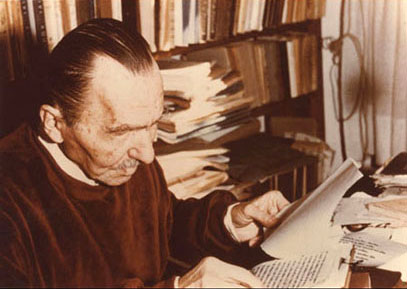

Kazantzakis devoted himself to writing: though he completed his translation of Homer’s Iliad and set to work on the Odyssey, wrote plays and collaborated with Kimon Friar on the English translation of his own Odyssey, novel writing was his main preoccupation.

It was at this time that he wrote almost all of his novels, with which he gained a worldwide following.

International Recognition

Though in Greece Kazantzakis did not succeed in being elected to the Academy of Athens, his fame abroad spread rapidly during the last decade of his life.

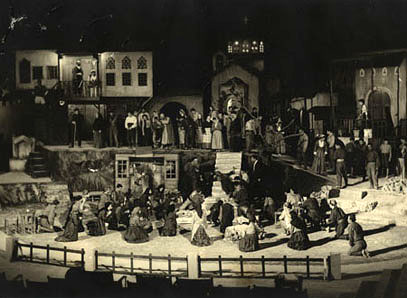

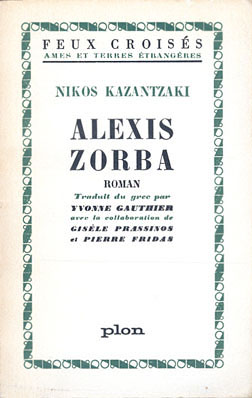

More and more translations of his works into European and other languages appeared; his plays were broadcast on European radio stations and performed in European theatres; in 1954 Zorba the Greek won the best foreign-language novel prize in France; W. B. Stanford dedicated a chapter of his book on the Ulysses theme to Kazantzakis’ Odyssey; Jules Dassin’s film version of Christ Recrucified won acclaim at the 1957 Cannes Film Festival.

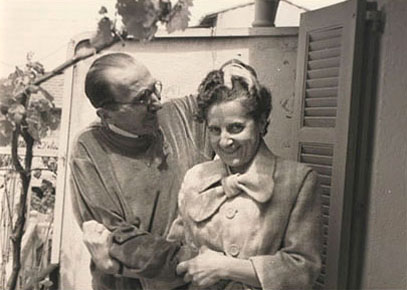

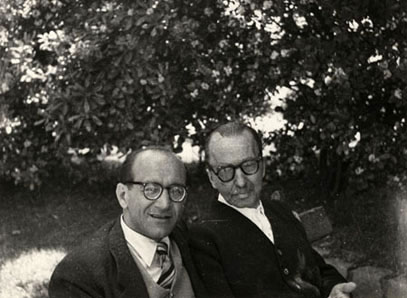

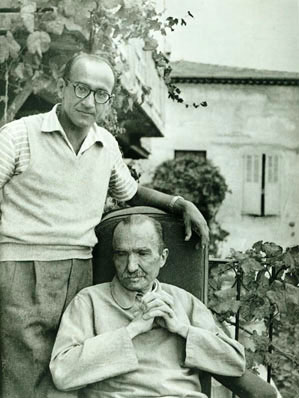

Kimon Friar

Kazantzakis and Friar first met in Florence in the summer of 1951. In the course of their brief conversation, the Cretan author discovered that his interlocutor understood him to the same extent and in the same way as Prevelakis.

Thus in 1954, when the American publisher Max Schuster sought to publish the Odyssey, Kazantzakis pointed to Kimon Friar as the only suitable translator. The collaboration and friendship between them began in Antibes in the summer of the same year, and continued up until Kazantzakis’ death.

Following the publication of the Odyssey, Friar continued to translate Kazantzakis, and over several years presented his work in lectures in America and Europe.

Prosecution

In 1953 the Church of Greece sought Kazantzakis’ prosecution on account of certain excerpts in Freedom and Death and The Last Temptation, before the latter was even published in Greece. The following year, the Pope placed The Last Temptation on the Catholic Index of Forbidden Books.

Numerous intellectuals and organisations defended the author, who telegraphed the Vatican with Tertullian’s phrase “I lodge my appeal at your tribunal, Lord”. The Ecumenical Patriarchate finally laid rumours and appeals regarding the excommunication of Kazantzakis to rest, claiming that the matter lay within the jurisdiction of the Church of Crete.